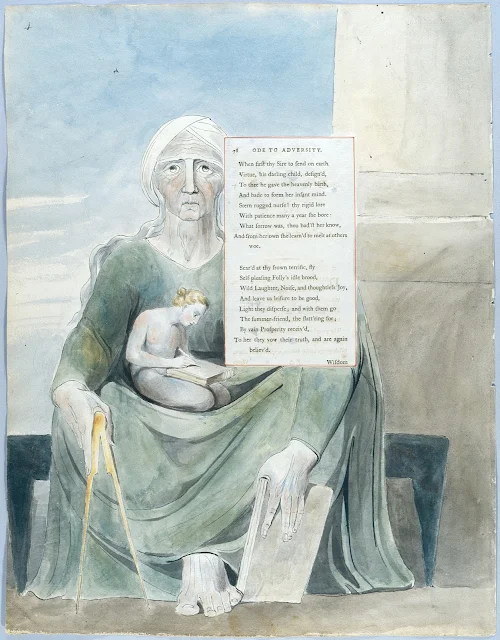

As I have written before, the great William Blake magnificently employed signs beyond mere words in his poetry. His powerful illustrations of verse add much additional meaning to his work. As I have noted before, his symbols such as words are greatly supplemented by other types of signs such as the iconic signs of his drawings. He applied these same principles in reverse in his great illustrations of the verse of other poets such as Thomas Gray and Edward Young. Such illustrated verse injects blocks of symbols within Blake's icons, and it can be fascinating to replace these blocks of others' symbols with additional iconic expressions by Blake himself. Blake's illustrations repeat common themes and can build on each other in such fascinating exercises. I think Blake would enjoy seeing others doing this with with his icons, and I would enjoy seeing how others might attempt the endless possibilities of such substitutions. For example, in the illustration above I have replaced Gray's verses about the "Stern Rugged Nurse" with one of Blake's illustrations of Urizen, the severe god of reason who traps the imagination with his compasses and strict categories. The compass in fact is an awful symbol for Blake. It's no accident that the "Stern Rugged Nurse" has one in her hand just like Urizen.

If we want to unleash Blake even more, we can compound the game. Rather than wonder imaginatively at the universe, poor Isaac Newton sits at the bottom of a deep body of water fixated on his compass and the little line it can draw on a mere piece of paper. Why not add him as well?

To go further still, why not combine illustrations of Gray's verse with illustrations of Young's? Blake understands that the fingers make a compass, too, and shudders when they are used in the way of Urizen, Newton, and the "Severe Rugged Nurse." Here's a possible combination of the above Urizen-Newton-Nurse with Blake's illustration of Edward Young's line "a span too short" from the once enormously-popular "Night Thoughts." Does the apparent father really think he can measure the new human life before him within the compass of his fingers? Should this not trouble us as much as Urizen, Newton, and the Nurse using their restrictive and blinding compasses?

For those who wish to see the original illustrated pages from Gray and Young, I insert them below:

For those wishing to explore Blake's art in more detail, the William Blake Archive provides a magnificent resource.

No comments:

Post a Comment